Scots pine: a genetic study reveals a close relationship between Ireland and Scotland

Pine

Pines (the genus Pinus) are mainly found in the Northern Hemisphere. We tend to associate pines with hostile, bleak and cold environments. A stark example of this is the case of Bristlecone pines (Pinus longaeva), which grow at high elevation in cold, dry habitats in the White Mountains of California. The scientific name “longaeva” is an indication of notable longevity. These pines are famed for being some of the oldest organisms in the world. One individual, named Methulaseh, has been aged to be at least 4,855 years old. However, some species of pine do stretch south into tropical areas and even into the southern hemisphere. One example of a more southern pine found in Honduras is the Thinleaf pine (Pinus maximinoi), a species cultivated in the National Botanic Gardens following from collections on a recent expedition.

Scots pine

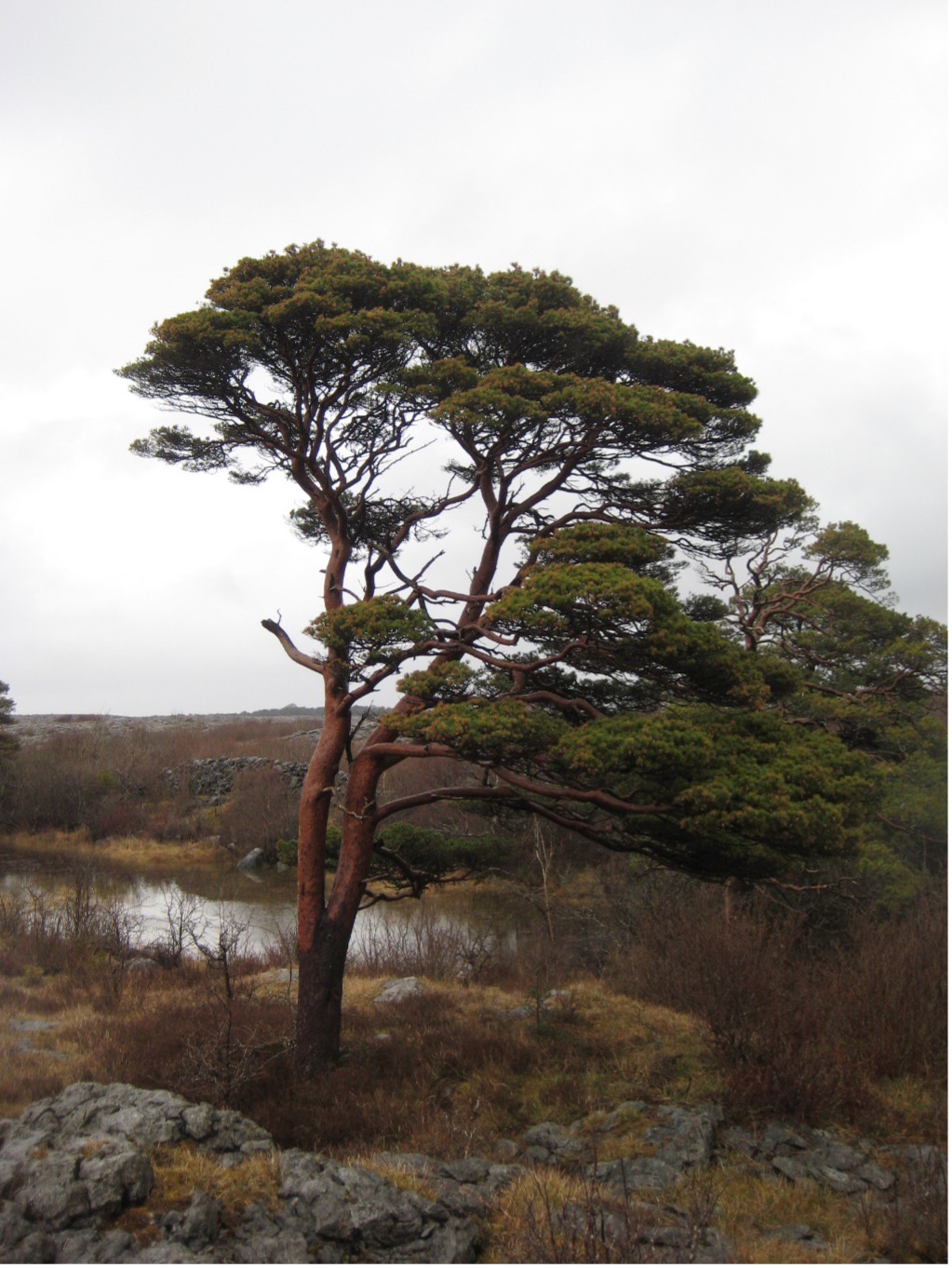

There are currently 134 accepted pine species across the world, Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) being one of them. Scots pine is a two-needled pine and is identifiable by its characteristic red-orange flaky bark. It is one of only three conifers considered native to Ireland, the others being Yew and Juniper. The name Scots pine is a bit of a misnomer as its distribution ranges from Ireland in the west all the way across into Russia in the east. This wide distribution range results in multiple local names for Scots pine and a large amount of variation. It tolerates a wide range of climatic and environmental conditions and while it can be found in parts of southern Europe it is found mainly in the temperate to boreal regions.

A brief history of Scots pine in Ireland

Scots pine was one of the first trees to recolonize Ireland about 9,500 years ago, after the retreat of glaciers following the last glacial maximum. The pollen records indicate it recolonised from the south and moved north-eastwards. This evidence has been used to suggest the possible movement of Scots pine from Ireland into Scotland during the post-glacial recolonization. This recolonization route and subsequent plantations from Scotland complicates the search for the origins of Ireland’s populations of Scots pine. It is difficult to disentangle the origin when the history of Scots pine is so convoluted. While an early coloniser, Scots pine did not dominate as it is not a strong competitor. It survives best on poor soils. As the climate changed over time Scots pine was put under pressure and suffered a decline. It was replaced by alder in lowlands and was smothered by peat, which formed blanket bog in the west. The iconic stumps of pine (often referred to as bog deal) are scattered across many bogs in the west showing the former extent of Scots pine. Although it was previously thought that Scots pine became locally extinct in Ireland, recent studies revealed a continuous pollen record from a site in Rockforest in the Burren. This suggests that at least some pine survived continuously since the recolonization. Scots pine was subsequently planted extensively from the 18th century onwards, and mostly from Scottish stock.

Scots pine in our landscape

Scots pine (Giúis in Irish) is listed in an 8th century Irish text as one of the seven noble trees “Airig Fedo”. It is also the first vowel in the Ogham alphabet (Ailm). While this would suggest it was an important tree historically, it is not very prominent in mythology or historical records in Ireland. As an example, placenames can be a fantastic glimpse into past landscapes, but there are very few placenames linked to Scots pine, certainly at least when we compare against oak (Dair) or willow (Saileach). Also, when looking at records of Scots pine uses in Ireland, often the most frequent example cited is that of wood taken from bogs - bog deal. The wood was taken from bogs for use as firewood, to be used as candles or for construction. Today we have established woodlands of Scots pine across Ireland and some scattered remnants on hilltops. However, most of these are recent plantations and landscape features from old estates. The iconic photo of Scots pine on an island in Derryclare Lough in Connemara, is a result of 19th century planting, not a glimpse back at an idyllic pine-covered landscape.

What genetics tells us about Scots pine in Ireland

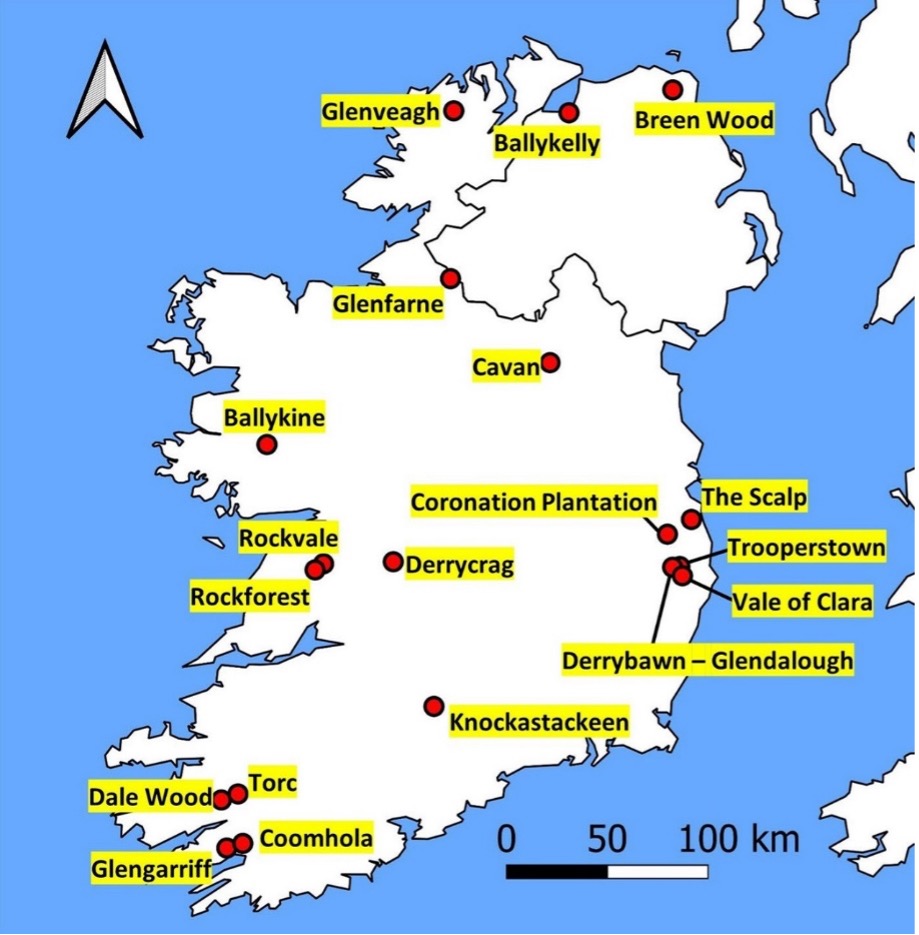

One piece of work that had been missing for years was a genetic study to test the origins of Irish Scots pine populations. Genetic studies can uncover hidden variation, which can be used to infer lineages and migration routes. This sort of a study could hopefully tell us about the origins of our pines and test their genetic uniqueness in a European context. A DAFM funded project was undertaken to sample 19 sites across Ireland[1]. Most of these sites were previously identified and described botanically in a study on the ecology of Scots pine in Ireland.[2]

The individuals sampled were genotyped with 28 different molecular markers in a large-scale facility in France using EU funding. These molecular markers are small, targeted pieces of DNA that can infer patterns and relationships. They are sufficiently variable to be informative and can help to determine genetic lineages and diversity. The markers we used are similar to those used for paternity tests in humans. However, one caveat when dealing with molecular markers in plants is that the level of investment and thus knowledge is much less compared to animal or human work. Thus, we sometimes have difficulty in differentiating individuals and populations at sufficient levels of resolution. We included some Scottish trees and some from France and Spain as outgroups to test against.

We anticipated that the genetic analysis might distinguish the Irish material from other material and that it might also distinguish the native site of Rockforest from the planted material elsewhere in Ireland. However, what was revealed by this study was less satisfying than that. There was a large amount of variation found across the island, but there was no “smoking gun” found at Rockforest or anywhere else. One site that did seem to be different was that of Dale Wood in Killarney. However, as we looked further at the data, the reason was that it had limited variation and so stood out on that basis, rather than having something uniquely variable. The reason Rockforest did not separate from the other populations is because of the close relationship with our native trees and the introduced trees from Scotland. The analysis showed that there was no separation between Irish and Scottish trees, they seem to be from the same gene pool.

However, the Irish and Scottish trees together separated from the continental populations. This shows that there is some difference between the western populations and those of southern and mainland Europe. The difficulty in determining patterns in Scots pine is that it is very variable. This is partially due to inherent genetic variability and also due to the wide dispersal of pollen across the landscape. While pine seed has limited ability to travel, the pollen can travel potentially hundreds of kilometres and so effective populations are very large and can span across fragmented landscapes. One particularly useful result from this project is that we can consider Scots pine introduced from Scotland like welcoming a distant relative rather than a new arrival. Irish and Scottish Scots pine are genetically quite similar.

[1] Belton, S., Cubry, P., Roche, J.R. and Kelleher C.T. (2024) Molecular characterisation of Pinus sylvestris (L.) in Ireland at the western limit of the species distribution. BMC Ecology and Evolution 24: 12. doi.org/10.1186/s12862-023-02181-3

[2] Roche JR et al. (2019). Recent findings on the native status and vegetation ecology of scots pine in Ireland and their implications for forestry policy and management. Irish Forestry 76:29–54.

Is that the final word?

The analysis we did was a process of grouping similar individuals into genetic lineages based on similarities. The simplest and most meaningful grouping we found was two groups, the Irish-Scottish group and the continental group. However, as we interrogate the data further we find more groups. These are not as meaningful statistically, but intriguingly, as we increase the number of groups other populations, including Rockforest start to separate out. This might mean that there is some variation in the trees at Rockforest that can differentiate them from the other populations in Ireland. However, to do this more work is needed. We are currently collaborating with colleagues in Scotland to look a little further into this and maybe we will find that smoking gun after all.

Article originally written by Dr Colin Kelleher.

Dr Colin Kelleher is the Keeper of the Herbarium at the National Botanic Gardens of Ireland, Glasnevin, Dublin 9. His research focuses on the origins and genetic diversity of the Irish flora, in particular the Irish tree flora.